Read the Report

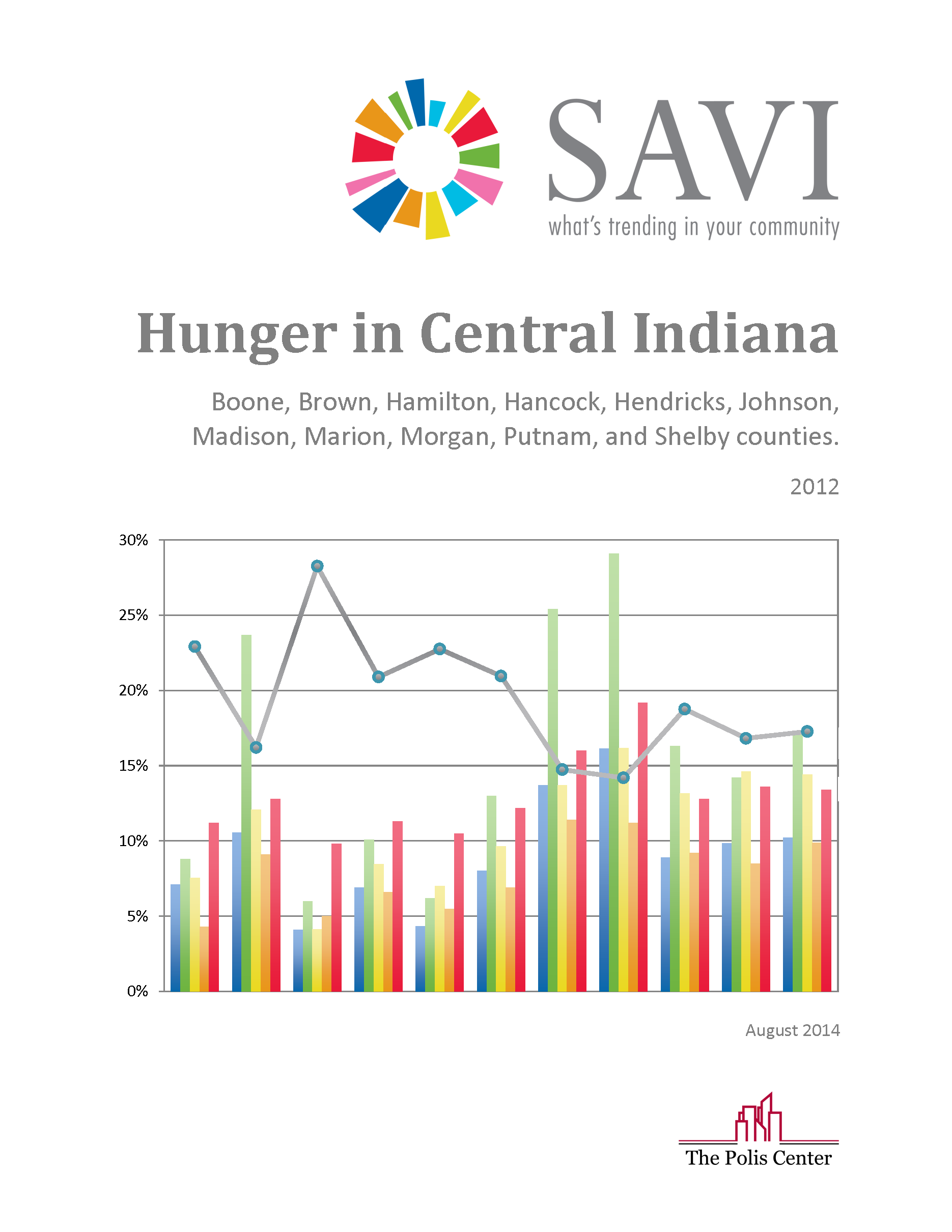

Central Indiana’s 11 counties are home to 30% of the state’s 6,537,334 Hoosiers. Of this population, 290,550 (15%) are food insecure.1 The Great Recession and the subsequent sluggish recovery have led to a 30% surge in American households confronting food insecurity, an increase of twelve million people facing hunger from 2007 to 20102. Despite these staggering numbers, most Americans are unaware of the severity of this growing problem. While it may seem that Indiana’s disadvantaged are well taken care of by the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program or SNAP (formerly food stamps) and other federal programs, the reality is that this funding, in conjunction with assistance from charitable agencies still does not meet many households’ food needs. Many families face the dilemma of choosing between food and other necessities.

Emily Bryant, Executive Director of Feeding Indiana’s Hungry (FIsH), Inc. explained that based on client surveys “46% indicated they had to choose at least once between paying for food or paying utility bills, 36% chose between paying for food or paying for medication or medical care, and 42% chose between buying food and paying the rent or mortgage… what is only more disheartening is that 13% of those surveyed reported that their children were hungry at least once in the last year because the family couldn’t afford more food.”3 As food insecurity grows in all American communities, it is vital that hunger relief organizations receive the funding and donations needed to accommodate this growth. Foremost, these agencies’ capacities must be expanded in order to operate as effectively as possible in the combat against hunger.

Awareness Is Half the Battle

One of the greatest challenges facing those in need in Central Indiana is the combination of lack of awareness of the resources available to them, and insufficient resources and capacity to accommodate this need. Many food pantries find themselves overwhelmed by the demand, which they often struggle to meet. Yet, those who show up to be served at food pantries are only a fraction of those in need. If all of Central Indiana’s food insecure knew about food pantries, soup kitchens, and emergency relief centers, those agencies would be unable to meet the spike in demand. This research has identified several strategies in resolving this problem.

At the opening of Johnson County’s Community Ministry Center in December 2013, Jeff Caldwell, special assistant to the governor, stated “a lot of people don’t realize when there’s a lot of food pantries doing these food drives… they think of, we’re sending this food to some third world country, we’re sending it out of state… there is a great hunger need all across our state… a million people in Indiana, who are hungry.”4 Awareness is the primary issue in the combat against hunger. Not only are the food insecure unaware of available help, but, as Caldwell explained, most Hoosiers are simply uninformed about the need within their own communities. In an effort to greatly raise awareness, this report has compiled an array of maps, graphics, charts, and first-hand testimonies in order to present a holistic account of Central Indiana’s hunger problem, from which the reader is free to draw his or her own inferences and conclusions.

Central Indiana’s

Assets:

- A substantial volunteer force

- A network of four food banks

- 350 food pantries

- Collaborative hunger relief organizations

Deficiencies:

- Many food pantries do not have the capacity to store perishables

- Hoosiers’ insufficient awareness of hunger, and many who are food insecure are uninformed about available resources

- Poor walkability and transit system limits the food insecure’s ability to seek assistance by foot or by bus

Timothy Gondola is a fourth-year student at Macalester College in St. Paul, Minnesota. He has spent most of his life in Indianapolis, though he’s lived in several US states, the Congo, and traveled to many European and African countries. He is a jazz and classical pianist, passionate about geography, and seeking to pursue a master’s degree in GIS at IU Bloomington. At Macalester, he is majoring in geography and minoring in music.

Timothy spent his 2014 summer as an intern at The Polis Center, developing this article and assisting with the SAVI website.